The global economy is stuck in a low-growth gear, largely because of aging populations, weak business investment, and structural frictions that prevent capital and labor from flowing to where it can be most productive.

As demographic pressures intensify and the green and digital transitions call for significant investment and resource reallocation across companies and industries, some countries are poised to fall further behind.

This makes it even more urgent to update the rules that shape how economies operate. Although specific policy priorities differ across countries, many economies share the need to ease market entry for new businesses, foster competition in the provision of goods and services, encourage workers to stay in the labor force, and better integrate immigrant workers.

Reforms like these need broad societal support, yet public discontent has mounted since the global financial crisis.

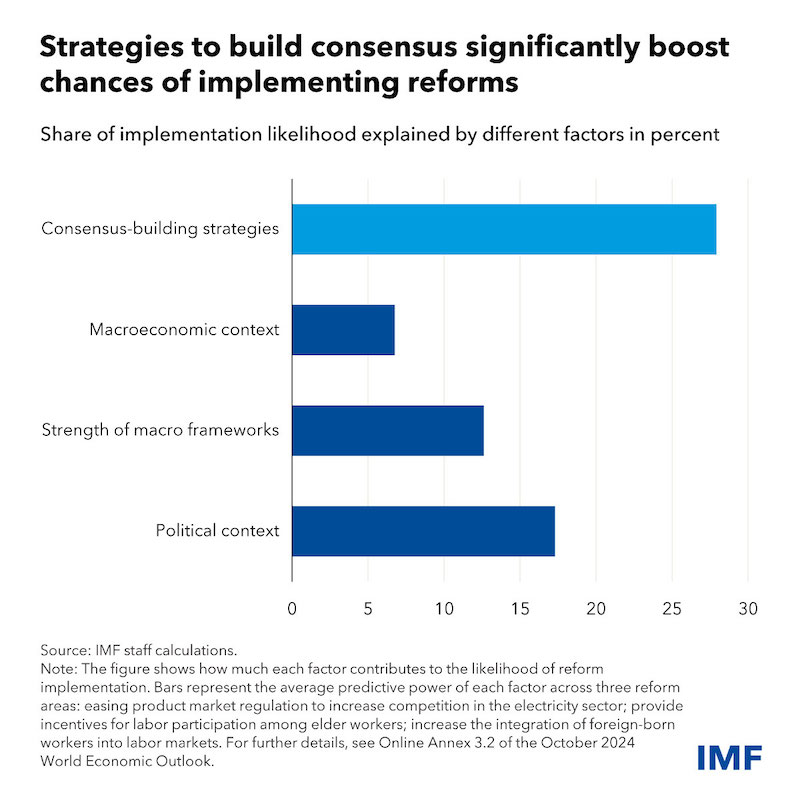

To build trust and public support, policymakers need to improve communication, engage the public when designing reforms, and recognize some people may need support if reforms hurt them, as we show in new analysis highlighted in a chapter of the latest World Economic Outlook.

Understanding social resistance

Our exploration of factors that shape public attitudes toward reforms shows that resistance often extends beyond mere economic self-interest. Personal beliefs, perceptions and other behavioral factors account for about 80 percent of support for reforms, according to our surveys of more than 12,000 people across six representative countries.

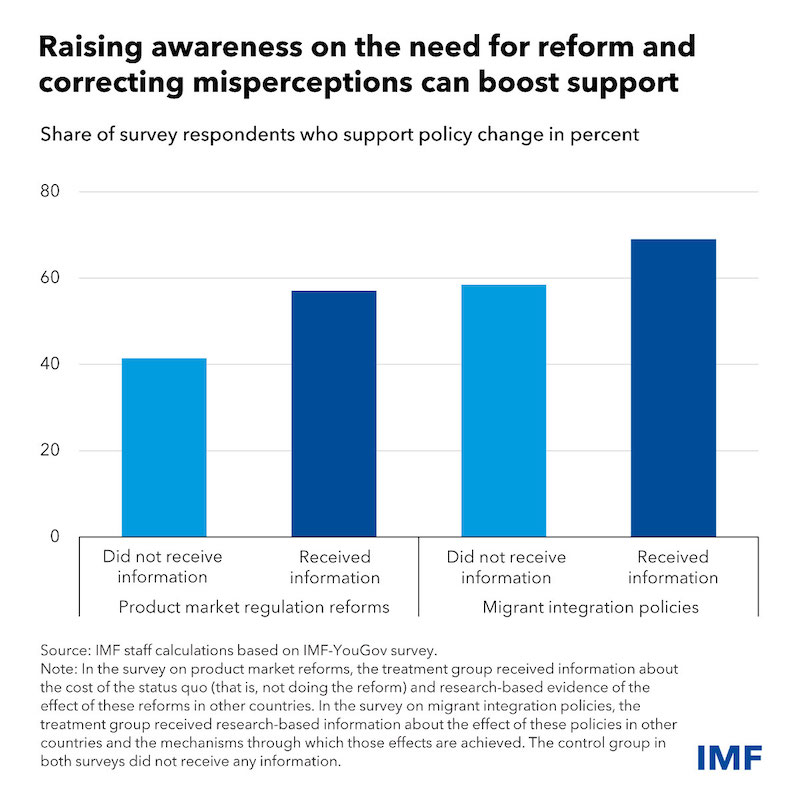

Crucially, knowledge and misperceptions about the need for reform and the effects of policies are the primary predictors of differences in policy support. This is important—and encouraging—because it offers a clear area for policymakers to act.

Perceptions of distribution and fairness are also critical. Reform opponents often worry more about the impact on their communities, particularly the most vulnerable, than on themselves. For example, opponents fear reforms to increase the role of the private sector in the electricity and telecommunications industries would make those services less affordable and reduce access for the poorest.

Lack of trust can also fuel opposition to reforms. People who say they oppose reforms, even if their concerns were to be adequately addressed by additional measures, mostly cite general distrust of the parties involved and doubts about the government’s ability to implement policy changes and mitigate any harms.

Strategies and tools to boost support

Our analysis suggests a multi-faceted strategy can ease resistance to structural reforms:

- Information: Effective communication is at the core of a successful reform strategy. This goes beyond advertising the reforms. Policymakers must convincingly explain the need for change, the expected effects, and how they might be achieved. Providing clear and nonpartisan information that corrects misperceptions significantly increases public support, we find. For instance, it led to more than 40 percent of those who were opposed to migrant integration policies in our survey to change their mind.

- Engagement: Dialogue between officials and the public should be two-way. Allowing people to help shape policies and voice concerns fosters a sense of community ownership over reforms, making individuals more likely to support proposed changes.

- Mitigation: Acknowledging that reforms may hurt some groups and addressing those concerns with tailored mitigating measures is essential to gaining public support. And it should be grounded in the previous pillars. Mitigations like temporary cash support or training programs should be informed by two-way dialogues between officials and citizens.

- Trust: The critical pillar on which all three above rely upon is trust. Effective communication requires confidence in both the message and the messenger. To build trust in the process, the engagement with citizens needs to start early, in the policy design stage. And reform design mechanisms should reassure the public that the government will deliver on mitigating commitments when reforms are done. Establishing credible and independent government bodies to conduct and validate policy analysis can be particularly helpful. First-generation reforms to address corruption and improve governance are fundamental to restoring faith in institutions.

Policymakers need to enhance their toolkit to build on this strategy and make reforms more acceptable to people. Public forums, pilot programs, and opinion surveys can help inform a two-way dialogue with citizens. Large-scale surveys, focus groups, and other participatory tools can identify concerns, craft adequate mitigations, and build consensus for reforms. New civic technologies, such as digital community engagement platforms, should also help more citizens participate.

Effective reform design requires thorough consultation, communication, and mitigation to compensate those who might be hurt. Better tools to encourage participation will help people better understand proposals and build the public trust needed to carry out vital economic reforms. These principles should also be reflected in the IMF’s periodic reviews of its program, surveillance, and capacity development initiatives.

—This article is based on Chapter 3 of the October 2024 World Economic Outlook, “Understanding the Social Acceptability of Structural Reforms.”

About the authors:

- Silvia Albrizio is an economist in the World Economic Studies Division of the IMF Research Department. Before joining the Fund in 2021, she worked at the Bank of Spain, at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development as well as at the European Central Bank

- Bertrand Gruss is a Senior Economist in the Research Department of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) where he works on the World Economic Outlook. Prior to that, he worked in the Fiscal Affairs, European, and the Western Hemisphere Departments of the IMF, and at the Central Bank of Uruguay.

- Yu Shi is an economist in the Research Department of the International Monetary Fund. She holds a Ph.D. in Economics from Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Source: This article was published by IMF Blog